Art about ‘issues’

I would never categorize my work as political or activist in any way, but some such issues might inform my work. Often this results from something I have read, and I read broadly, primarily non-fiction. One such example is a series of intaglio prints I made after discovering the first person diaries of Great White Hunters of the British Empire.

I was probably searching for images and information about animals that I am not easily able to draw from life. I am fine with doing this because I have no safari travel budget, live far from a zoo, have interest in animals that would never be in a zoo in the first place, are dangerous, rare, extinct, or are sensibly in hiding. A more important reason is this: the mythology of animals, the way we picture them in our minds, including associations poetic or literary, is often the most interesting thing I am after!

The diaries were compelling, horrific, and transparent to a reader from the 21st Century. They presented the Great White Hunters as brave, skilled, manly and adventurous (of course) and created an image of an elegant, refined way of life in exotic circumstances that the authors hoped would reflect well on their character and grit. The transparency I most appreciated was unintended, however, and came through the details. The casual lists of shipped supplies from Britain: crumpets and orange marmalade, gin and crystal, heavy writing desks, bathtubs and oriental rugs for the floors of their “rustic” bush camp wall tents. Photos revealed dozens of black porters carrying all this on their backs through the bush, on foot, while the hunters rode. The manner in which the hunters referred to their native employees was disgustingly arrogant, while the detail revealed that usually it was the skilled trackers and guides that found the prey, and all but shot the animal themselves. They recorded details of how they had others do the hard work of butchering or skinning and then crating and carrying the spoils, usually just the head, pelt, or tusks. How those crates must have smelled in the heat! Never an inkling of understanding of how the indigenous people viewed or valued these creatures, much less how they viewed the “hunters” themselves! Accounts of big game hunters in the Arctic presented the same mythologies, and exploited the same indigenous knowledge and skill.

I was interested in the way the animals were later presented, as trophies, and all of what that means, to the hunter and to the audience. The taxidermied and mounted head, the Bengal Tiger rug, the animal’ defensive weapons (tusk, claw, tooth), the stretched skin. I had learned while in Alaska that the skinned bear carcass, hung upright, eerily resembled a flayed man. The indigenous People were of course intimately knowledgeable with the bear and saw the upright posture bears posture as part of their relative’s character and position in the living world. The way they viewed the bear was as the bear was, in the physical world and the metaphysical world and the long-Earth-time-frame world, a wholistic and relational full picture. This reinforced the superficiality of the Great White Hunter’s understanding as simply skin deep, if that. The animal was actually sort of incidental to the hunter’s presentation of self.

This got me thinking of representation of animals, as symbols of power, or totems of masculinity, of domination and hierarchy, and that colonial imperative to maintain total control. I certainly did not want my imagery to reinforce that horror!

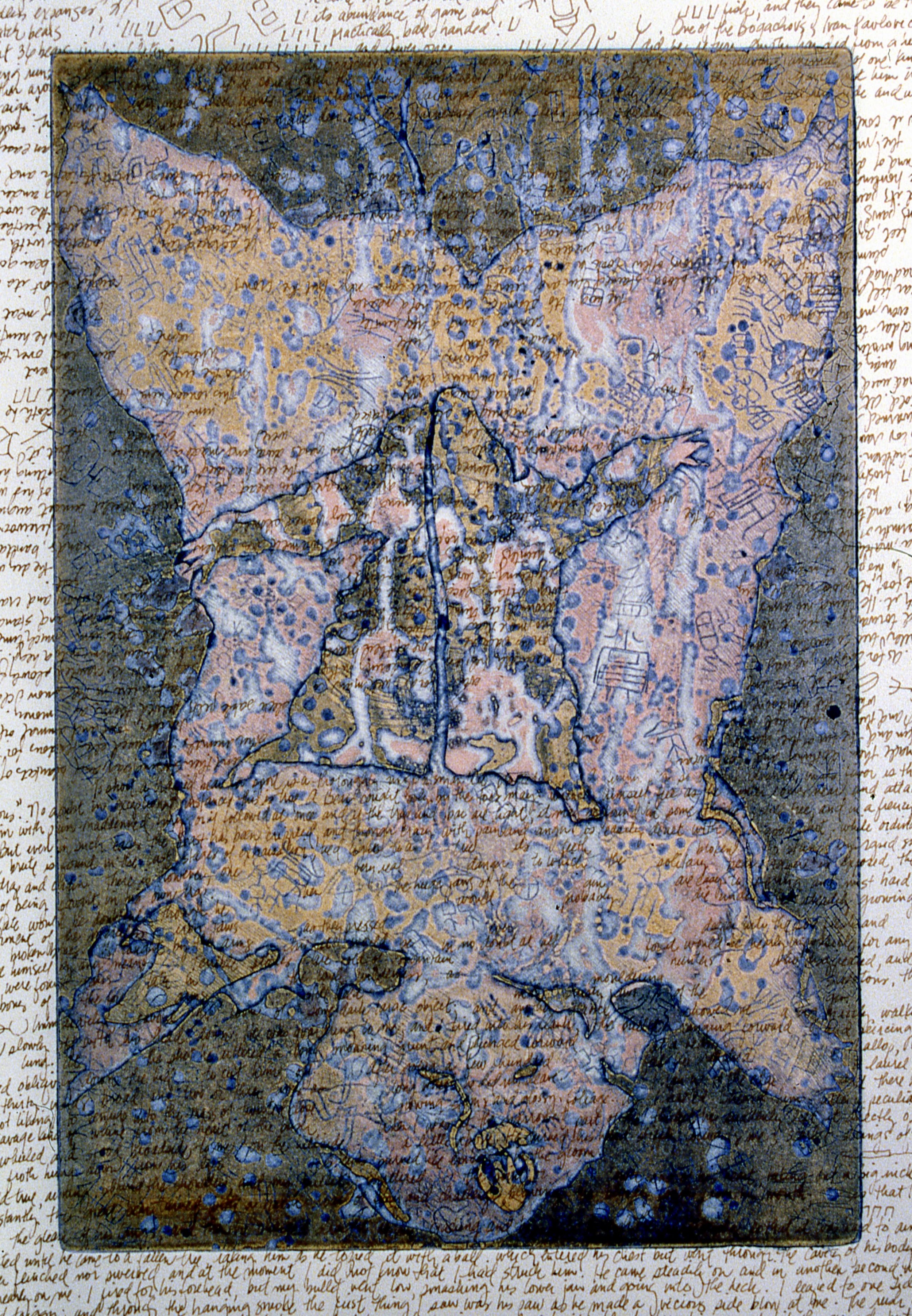

My trophy print series aimed for richly colored and textured iconic animal portraits. I buried in the surface patterns, layers, symbols, and runes to represent the animal in a reverential way. I wanted to hark back to all the generations of that species from the very beginning! I wanted symbols of human meaning-making embedded as enhancements, for a creature that needed no enhancements.

Then, I pulled “ghost prints” of the full-color plates to add a veil of history through which to see the animal another way. The veil was a screen of cursive fragments of text from the diaries. I added this by hand with an old fashioned fountain pen and a permanent version of the old brown ink used then. The pale ghost image loses the immediacy of full color and comes into and out of focus along with the evocative words.

Both the trophy animal and the Great White Hunter are now long dead. The prey species are hanging by a thread to survival in a world still dominated by the human species. My images acknowledge this, but the focus is on the animal as the dignified one.